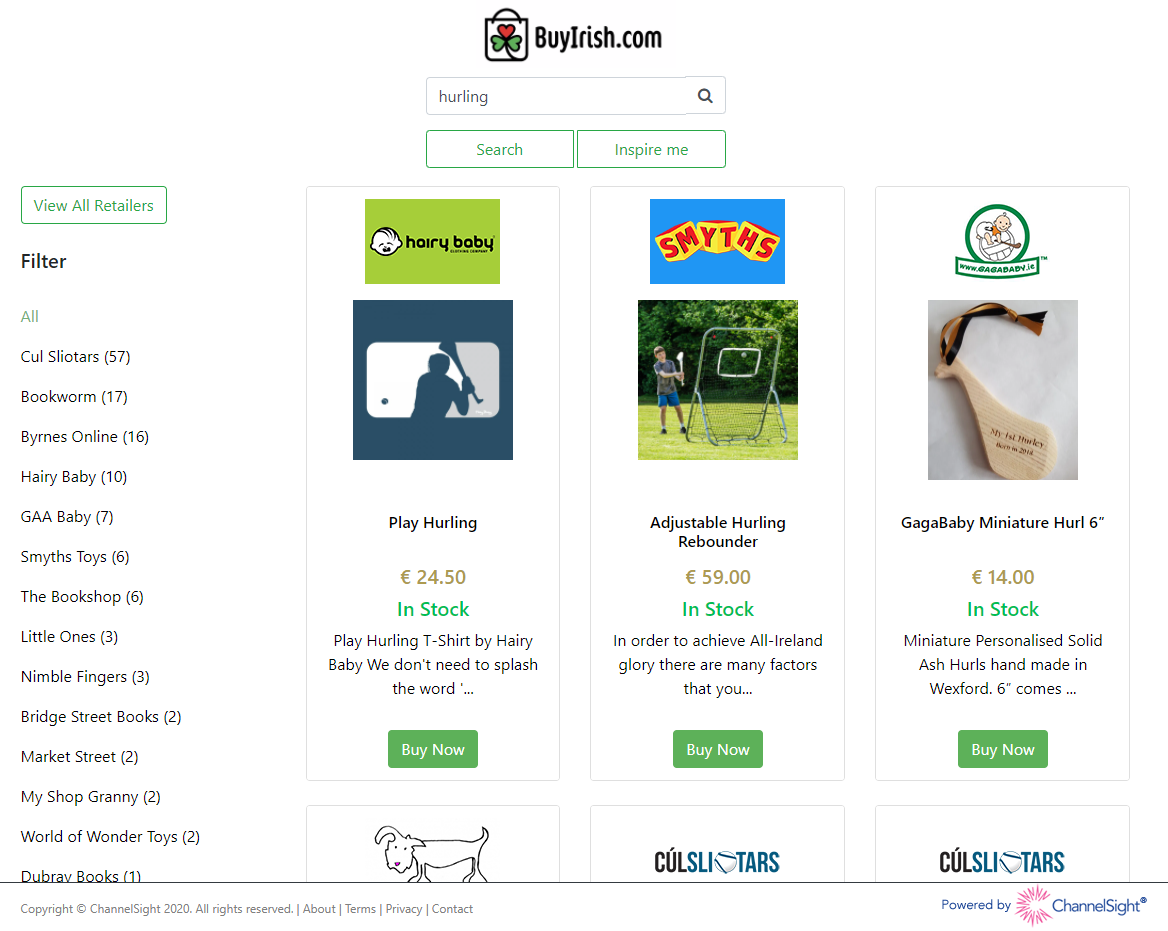

Over the past 6 months, I’ve been overseeing the design and implementation of a number of new projects for ChannelSight’s Buy It Now platform. One of the key technologies at the center of these projects is Cosmos DB, Microsoft’s globally distributed, multi-model database.

We’ve been moving a variety of services, which previously sat on top of SQL Azure, over to Cosmos DB for a variety of different reasons; performance, ability to scale up/down fast, load distribution; and we’re very happy with the results so far. It’s been a baptism by fire, involving a little bit of trial and error, and we’ve had to learn at lot as we went along.

This week I ran a workshop for our Dev team on Cosmos DB. Partitioning was the area we spent most time discussing and probably THE most important thing to spend time on, during the planning stages, when designing a Cosmos DB Container. Partitioning defines how Cosmos DB internally divides and portions up your data. It affects how it’s stored internally. It affects how its queried. It affects several hard limits you can hit. And it affects how expensive it is to use the service.

Getting your partitioning strategy correct is key to successfully utilizing CosmosDB; getting it wrong could end up being a very costly mistake.

Microsoft provides some guidance on partitioning, but that didn’t stop me from making a number of errors in my interpretation of what a good partitioning strategy should look like and why.

What is partitioning?

First, it’s important to understand what paritioning is in relation to Cosmos DB, and why it needs to partition our data. Cosmos DB lets you query your data with very low latency at any scale. In order to achieve this, it needs to spread your data out among lots of underlying infrastructure along some dimension that you specify. This is your partition key. All rows or documents which share the same partition key will end up stored and accessed from the same logical partition. Imagine a very simple document like so:

{

"id":1

"name":"Eoin"

"city":"Dublin"

}

If you decided to specify /city as the partition key, then all the Dublin documents would be stored together, all the London documents together, and so on.

How is Cosmos DB structured?

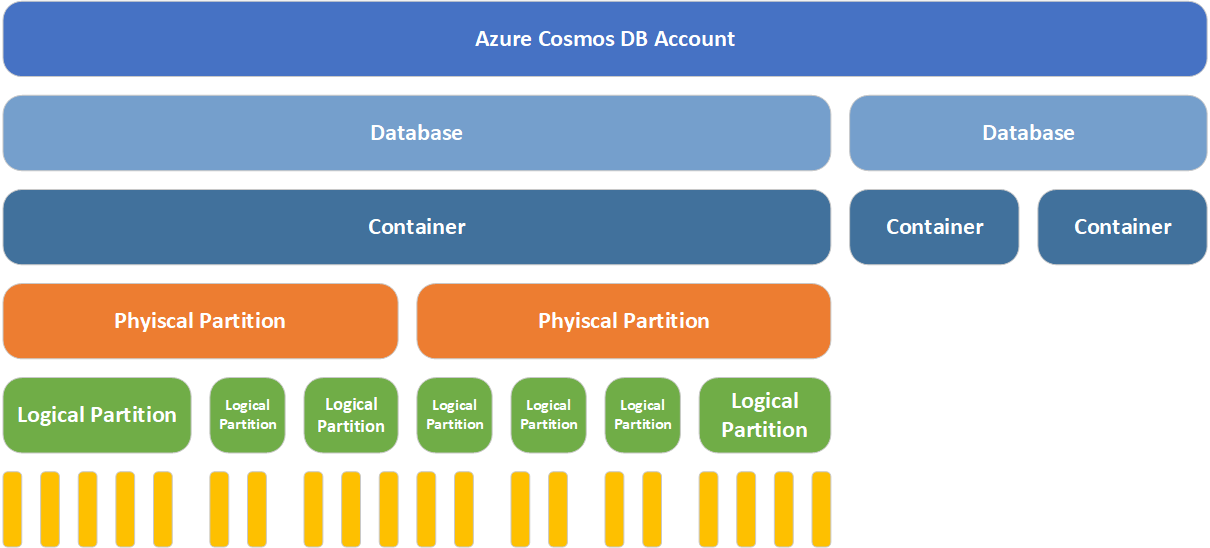

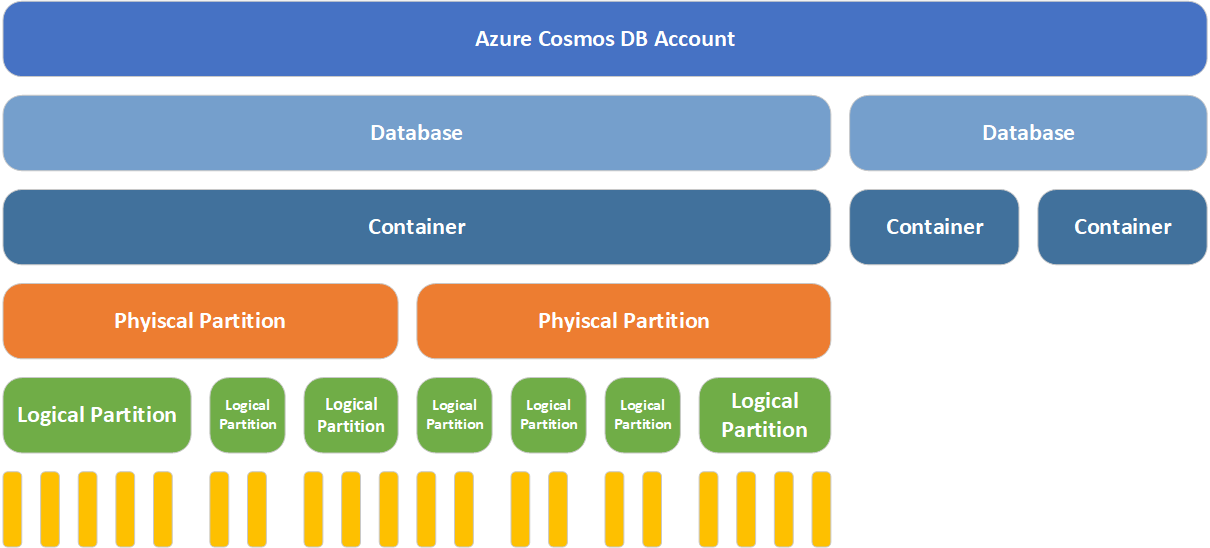

Before we get down to the level of partitions, lets look at the various components that make up your Cosmos DB account.

- The top layer in the diagram, represents the Cosmos DB account. This is analagous to the server in SQL Azure

- Next is the database. Again, analgous to the database in SQL Azure

- Below the database, you can have many containers. Depending on the model you’ve selected your container will either be

Collection or a Graph or a Table

- A container is served by many physical partitions. You can think of a physical partition as the assigned metal that serves your container. Each physical partition has a fixed amount of SSD backed storage and compute resources; and these things have physical limitations

- Each physical partition then hosts many logical partitions of your data

- And each logical partition, in turn holds many items (documents, nodes, rows)

We're using CosmosDB with the SQL API and since we're coming from a SQL Azure background, there is somewhat of a SQL/Relational slant on the opinions below. I'll be talking about `Collections` and `Documemnts` rather than more generically but the same principals apply to a Graph or Table either.

When you create a new collection, you have to provide it with a partition key. This tells the database along what dimension of your data (what property in your documents), it should split the data up. Each document with a differing partition key value will be placed in a different logical partition. Many logical partitions will be placed in a single physical partition. And those many physical paritions make up your collection.

Parition Limitations

While logical partitions are somewhat nebulous groupings of like documents, physical partitions are very real and have 2 hard limits on them.

- A physical partition can store a maximum of 10GB of data

- A physical partition can facilitate at most 10,000 Request Units (RU)/s of throughput.

A physical partition may hold one or many logical partitions. Cosmos DB will monitor the size and throughput limitations for a given logical partition and seamlessly move it to a new physical partition if needs be. Consider the following scenario where two large logical partitions are hosted in the one physical partition.

| Physical Partition |

Logical Partition |

Current Size |

Current Throughput |

OK |

| P1 |

/city=Dublin |

3GB |

2,000 RU/s |

|

| P1 |

/city=London |

6GB |

5,000 RU/s |

|

Cosmos DB’s resource manager will recognise that entire P1 partition is about to hit a physical limitation. It will seemlessly spread these two logical partitions out to two seperate physical partitions which are capable of dealing with the increased storage and load.

| Physical Partition |

Logical Partition |

Current Size |

Current Throughput |

OK |

| P2 |

/city=Dublin |

5GB |

4,000 RU/s |

|

| P3 |

/city=London |

7GB |

8,000 RU/s |

|

However if a single logical attempts to grow beyond the size of a single physical partition then you’ll receive an error from the API. "Errors":["Partition key reached maximum size of 10 GB"]. This would obviously be very bad, and you would need to reorganise and repartition all this data to break it down into smaller partition by a more granular value.

| Physical Partition |

Logical Partition |

Current Size |

Current Throughput |

OK |

| P2 |

/city=Dublin |

5GB |

4,000 RU/s |

|

| P3 |

/city=London |

10GB |

10,000 RU/s |

|

Microsoft provides some information here on how the number of required partitions are calculated but lets look at a practical example

- You configure a collection with 100,000 RU/s capacity T

- The maximum throughput per physical partition is 10,000 RU/s t

- Cosmos allocates 10 physical partitions to support this collection N = T/t

- Cosmos allocates key space evenly over 10 physical partitions so that each holds 1/10 of logical partitions

- If a physical partition P1 approaches it’s storage limit, Cosmos will seemlessly split that partition into P2 and P3 increasing your physical partition count N = N+1

- If you return later and increase the throughput to 120,000 RU/s T2 such that T2 > t*N, Cosmos will split one or more of your physical partitions to support the higher through put

Data Size, Reads & Writes

In an ideal situation, your partition key should give you several things

- An even distribution of data by partition size.

- An even distribution of request unit throughput for read workloads.

- An even distribution of request unit throughput for write workloads.

- Enough cardinality in your partitions that overtime, you will not hit those physical partition limitations

Finding a partition strategy that satisfies all of those goals can be tricky.

On the one extreme, you could choose to place everything in a single partition but this puts a hard limit on how scalable your solution is as we’ve seen above. On the other hand you could put but every single document into it’s own partition, but this might have implications for you if you need to perform cross partition queries, or utilize cross document transactions.

So what is an appropriate partition strategy?

When building a relational database the dimensions upon which you normalize or index your data tend to be obvious. 1:Many relationships are obvious candidates for a foreign-key relationship; any column that you regularly apply a WHERE or ORDER BY clause to becomes a candidate for an index. Choosing a good partition key isn’t always as obvious and changing it after the fact can be difficult. You can’t update the partition key attribute for a collection without dropping and recreating the collection. And you can’t update the partition key value of a document, you must delete and recreate that document.

All of the following are valid approaches in certain scenarios but have caveats in others.

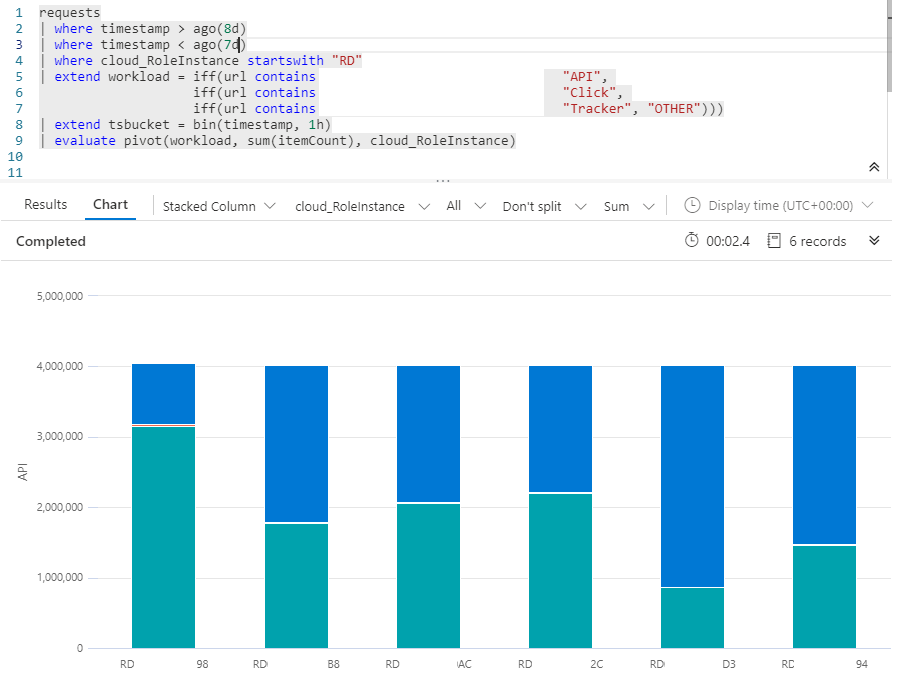

Partitioning by Tenant Id or “Foreign Key”

One candidate for partitioning might be a tenant Id, or some value that’s an obvious candidate for an important Foreign Key entity in your RDBMS. If you’re building a product catalog, this might be the Manufacturer of each product. But if you don’t have an even distribution of data/workload per tenant, this might not be a good idea. Some of our clients have 100 times more data and 1000 times more traffic than others. Using manufacturer Id uniformly across the board would create performance bottle necks for some of the bigger clients and we would very quickly hit storage limits for a single physical partition.

Single Container vs. Multiple Containers

Another option for dividing data along the “Tenant” dimension would be to first shard your application into one-container-per-tenant. This will allow you to isolate each tenants data in completely seperate collections, and then subsequently partition that data along other dimensions using more granular data points. This also has the benefit that a single clients workload won’t impact your other clients. This did not make sense for us, as with a 1000 RU minimum per collection, the majority of our smaller clients would not hit that limit, and we couldn’t have passed on the cost for standing up that many collections.

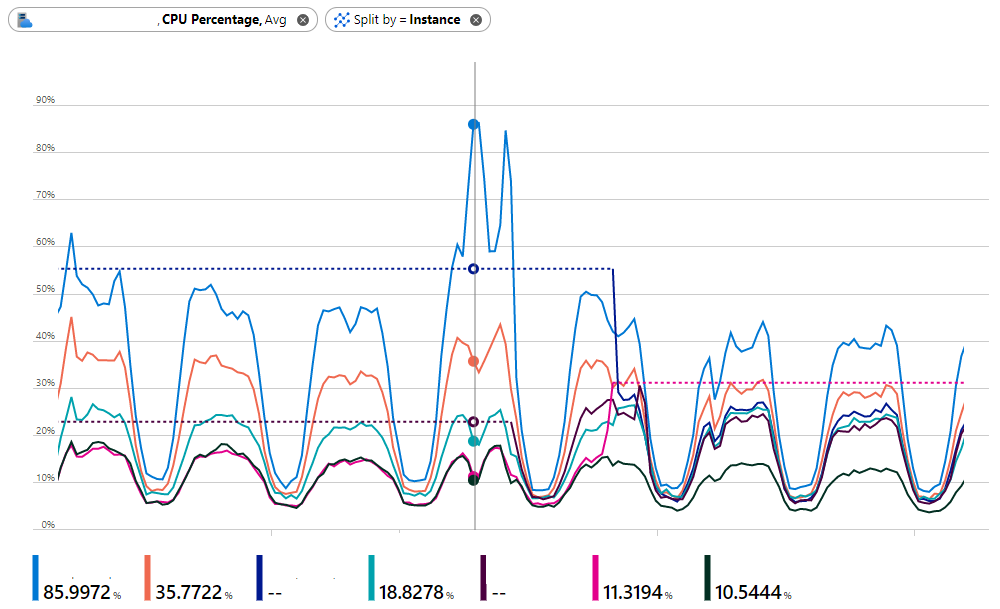

Partitioning by Dates & Times

You could also partition your data by a Date or DateTime attribute (or some part of). If you have a small consistent write workload of timeseries data, then partitioning by some time component (e.g. yyyy-MM-dd-HH) would allow you to subsequently query or fetch sets of data efficiently in 1 hour windows. Often, however, this kind of timeseries data is high volume (audit logs, http traffic) and as such you end up with extremely high write workloads on a single partition (the current hour) and every other partition sitting idle.

Therefore it often makes more sense to partition your data (logs) by some other dimension (process id) to distribute that write workload more evenly.

Partitioning by a Hybrid Value

Taking the above into consideration, the answer might involve some sort of hybrid value mixing data/data points from serveral different attributes of your document.

An application audit log for your platform might be partition data by {SolutionName}/{ComponentName} so that you can efficiently search logs for one area of your system. If the data is not needed long term, then you could specify time-to-live values on the documents so that they self-expire after a rolling period of days

HTTP traffic logs, for impression and click data might be partitioned by {yyyy-MM-dd}/{client}/{campaign} so that data and write workloads are partitioned at the level of an individual client and individual marketting campaign for a given day. And then you can efficiently query that data for specific date ranges, clients and campaigns for reporting aggregation later.

Dynamic Partitioning for Multiple Documents Types

For our solution we had a very specific requirement for our product search query. For a given Manufacturer’s product SKU, we wanted to look up all the retailers that carried that product. In the end we settled on the following strategy:

Put all documents in a single collection

We started out with essentially two types of documents

- A

Product document, which contained a SKU & Manufacturer data

- A

Retailer Data document, which contained a reference id to the Product document

Use a common base entity for all documents

We then implemented a small abstract base class which all documents would inherit from. The PartitionKey string property is used as the partition key for the entire collection.

public abstract class CatalogBaseEntity

{

[JsonProperty(PropertyName = "id")]

public string Id { get; set; }

public string PartitionKey { get; set; }

public abstract string Type { get; }

}

Use different value sets for the Partition Key based on Document Type

For our Product documents, the value of the partition key is set to Manufacturer-<UniqueManufacturerId>. Since the product meta data for a single product is quite small, we’ll never hit the 10GB storage cap for a single manufacturer.

For our RetailerData document, the value of the partition key is set to Product-<ProductDocumentId>.

Querying the API for Product data

We now have a very efficient search system for our product data.

When our API receives a SKU query, we’ll first do a lookup for a Product document for a single manufacturer + sku. This is a single, non-partition-crossing query.

Next, we take the ID of that Product document and do a subsequent query for all the associated Retailer Data documents. Again, since this partitioned by the Product.Id it’s a non-partition-cross-query and limited to a finite set of results.

Hopefully that was a useful insight into partitioning data in Cosmos DB. Would love to hear other peoples experiences with it. And also, if there’s anything I’ve misinterpretted, drop me a note in the comments so I can correct it. Like I said, this has been a big learning experience for us here.

Eoin Campbell