I want to be a software architect

For the last 6 months I've been working as a software architect for ChannelSight here in Dublin. I'm really enjoying it and lucky in that I have a fairly broad remit here. But what is "Architecture". What do I do? If you want to be architect:

- What does that career path look like?

- What skills do you need?

- What can you expect?

In interviews with senior developers, they'll mentioned that a role as an architect is a career goal for them, but when asked how they're trying to achieve that goal, they flounder.

I've held roles with junior, mid-level & senior development titles. Then I moved into lead & management roles with a mix of architecture, project management and people management. I think this is a natural progression for developers. The opportunities for progression for a senior developer might involve staying in development, moving into architecture, taking a managerial position, or some combination of the three.

Personally, I wanted to progress along a technical path. Most importantly I enjoy architecture. I like designing things, doing research, coming up with ideas and overseeing the creation of new software.

What's in a Job Title?

My full job title is Senior Technical Architect. That title will mean different things to different people. Some might call it Software/Solution Architect or Technical Lead or something else. Depending on the software/products you build, there might be slight discrepancies in what the job entails. Depending on company size, the responsibilities in the role may differ.

I've only worked in SMEs with 20-60 employees, so the architecture roles I've held have also had tendrils into client engagement, requirements, team leading, project management and hiring. In a larger organisation, an Architect's role might be more focused on designing the software.

So what can you expect as a Software Architect?

You need to be able to design software

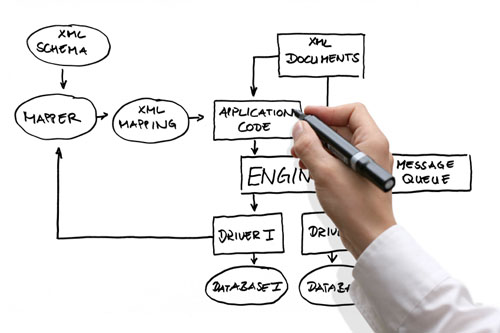

And obvious one, but you need to be able to design software. This might mean just the software itself or the systems and infrastructure that go with it. Ultimately, you need the capability to look at a problem, and think up an appropriate software solution for it.

- Do you understand the business and domain problem?

- Do you know the software & architectural patterns that can be applied?

- Do you have an appreciation for the the function and non-functional requirements you need to satisfy?

Sometimes the answer to these questions will be "No" and you'll start from a position of disadvantage. Part of the challenge is being able to figure out those answers.

You'll need to draw on your experiences in previous projects. You'll need to do research. And ultimately when you've pulled all the various pieces together, you need to assemble them into a design that meets the needs of your client or company.

You are responsible

Not to say you don't already have responsibilities, but as an architect, there comes an additional level of responsibility and the buck stops with you. You are responsible for the designs you put forward. If you propose a solution that won't work, and your team builds that solution, then the responsibility if it fails is yours.

In smaller companies, you may have other responsibilities too. You may have to:

- ... engage with clients, and thus are responsible for the company's image.

- ... participate in hiring and are in part responsible for the composition and capability of the development team.

- ... run training and up-skill workshops.

With more seniority, comes more responsibility and you need to step up.

You need to make time for thinking

There will always be an amount of straight forward, humdrum project work involving good old n-tier architectures that most developers are pretty comfortable with. But for other projects, I need to put time aside to get my head around the task. I need time to think.

I use mind-maps to brainstorm out my thoughts. I eek out space in my day (sometimes out-of-hours) with a whiteboard or a notepad and scribble things down. You should bring others into this thinking time as well. Some of the best solutions I've come up with in the past weren't a single eureka moment on my own. They happened with two or three smart people in the room with me as we all collaboratively came up with a solution that we could confidently stand over.

It's helpful to have some resources to hand too. Having a copy of the Gang of Four: Design Patterns on your (e-)book shelf is a good idea. Since I work on the .NET stack and Azure Platform, knowing the .NET tools and frameworks, and being able to refer back to Cloud Architecture Patterns is helpful also.

You need to be a good communicator

As an architect, expect to have to talk... a lot. Pre-design, you'll talk to clients, business analysts and senior management to get the information you need. After you've create a design, you need to communicate it to everyone; first to get buy in from the stakeholders and second so that your team understands what they've been tasked to build. You'll attend a lot more meetings (workshops, requirements, reviews etc...) and be expected to engage with a much broader group in your company.

You'll present more often; sometimes a pre-prepared PowerPoint deck to the business, pitching your ideas; other times presenting to tech staff, explaining the solutions there and then on the whiteboard.

You'll need to explain your ideas in varying levels of complexity/detail. While talking with developers, those conversations might be technical, getting into the nitty-gritty of a design. Other times, you may have to take an Explain-It-Like-I'm-5 (ELI5) approach with business colleagues, who don't have the same technical grasp, but need a higher level understanding.

Finally, you need to be comfortable fighting your corner. There is a balance to be struck between a pragmatic architecture (avoiding over-architecture/unneeded complexity) and ensuring it is for purpose (avoiding a sub-par solution due to some other constraints). You must be comfortable having these discussions and be able to make your case with facts and evidence to back it up.

You will write more documents and less code

A big part of that process is getting your designs and ideas across to other people. You'll spend more time writing docs and less time writing code. My role now involves writing specifications, drawing UML diagrams, typing up Jira Backlog Items and filling out Confluence documentation so that others have the information they need. This is at the expense of getting to write code on a day to day basis myself.

As a result, some ring rust has been creeping into my capabilities as a developer. When I do have the luxury to write code, it takes me longer to do things than it did in the past, and because of time constraints and priority juggling, it's very rare I can get into a flow.

You need to be able to write requirements

You should be comfortable capturing & writing requirements. In a larger organisation, the responsibility to write a Business/User Requirements Specification document might be the job of a dedicated business analyst/project manager. Or it might fall upon you. You might contribute to functional requirements specs, or document out use-cases or user-stories. You need to understand how to capture non-functional requirements. On a brown-field project, you may need to research what's there already and conduct a gap analysis.

At later stages in the design phase, you'll need to be comfortable creating a software design document or technical specification that explains the technicalities of what you plan to build and how it will satisfy those business/functional requirements.

You need to know how to frame the requirements and how to present your proposed solution to the stakeholders. The may be many approaches that could be taken. The design you put forward will affect where in the Good-Fast-Cheap triangle the implementation will land. If there are time, cost or quality considerations to take into account, these need to fit into your thinking and design rationale.

If your architecture role also carries some PM responsibilities, you may need to go back to stakeholders with recommendations, some that might not be popular. Perhaps it's just not possible to meet their requirements within the constraints they've set out and some prioritization approaches like MoSCow (Must-Should-Could-Would) may be necessary to decide what requirements will and won't be met during the (initial) implementation phase.

You need to let go

Something I find challenging is having to take a step back from the implementation and let others get on with it. If you've come from a senior dev background, you've probably contributed to both design and implementation. You may have strong opinions on what the code/implementation should look like. But that might not be your job anymore. You can still be involved, maybe in an oversight capacity, maybe guiding more junior developers on how to do something, or taking part in code-reviews or maybe you can contribute to some small part of the implementation if you're lucky.

For the most part, you won't have the time and bandwidth to embed yourself in the day to day implementation. You need to let go and hand the implementation reins over to the developers. And you need to trust that those developers are capable of delivering your vision for the solution.

This might make you feel like you're becoming a jack-of-all trades and master of none. But that's OK. Your job as architect is to focus on the big picture. To see the overall solution.

You need to be able to self-improve and do research

As a closing thought, you need to find a way to improve as an architect. The software development landscape is constantly evolving. New technologies are constantly introduced. New methodologies will gain and fall out of favor. New ecosystems will emerge (mobile, wearables, iot etc...) and new regulations will appear (GDPR and ePrivacy).

If you're lucky, your organisation may have a way to support you. Perhaps there's an architecture team/board where new ideas can be discussed. Or perhaps there's dedicated time put aside for R&D. But in smaller companies, you may be seen as the "most senior developer" and not have anyone else in your immediate circle of colleagues that you can learn from on a day to day basis.

You'll need to find away to pull yourself up by your own bootstraps. That may involve:

- reading books & blog posts

- listening to podcasts

- finding time in your professional or personal life to try out new things

- testing and coding with new technologies and frameworks

If you don't have someone in your company that you can go to, then perhaps you can find a mentor outside. An ex-colleague or friend who's further along their career path that can guide you or at least act as a sounding board

There are membership communities like the International Association of Software Architects where you can find further material on software architecture. There are formal training and certification paths like the TOGAF Certification where you can get a recognized qualification as an enterprise architect. And within the Microsoft world, there are MCA (Microsoft Certified Architect) paths that you can take, and several Application/Solution level certifications like Architecting Microsoft Azure Solutions.

Good Luck

~Eoin Campbell